Colonial Exploration: the Early Years in Broken Bay and the Ku-ring-gai Region

by

SydneyOutBack.com.au :

March 15th, 2016

Within 10 years of the First Fleet’s arrival in Australia on 26 January 1788, rapid exploration and settlement radiated out from Sydney Cove. In that decade, relations between colonial immigrants and the Indigenous population took several turns for the worse. Broken Bay and the region we now call Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park was one frontier where cordial first impressions gradually deteriorated, with devastating end-effect on the local Guringai people.

Within 10 years of the First Fleet’s arrival in Australia on 26 January 1788, rapid exploration and settlement radiated out from Sydney Cove. In that decade, relations between colonial immigrants and the Indigenous population took several turns for the worse. Broken Bay and the region we now call Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park was one frontier where cordial first impressions gradually deteriorated, with devastating end-effect on the local Guringai people.

So, how did it all begin and why did it unravel so quickly?

- Captain James Cook passed by in 1770 observing broken land from below the deck. This, he named “Broken Bay” and continued sailing northward along the coast.

-

Captain Arthur Phillip in Botany Bay, NSW (Picture: Museum of Sydney Collection)

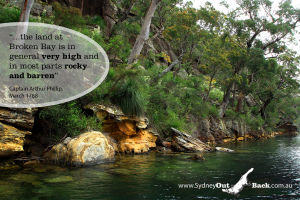

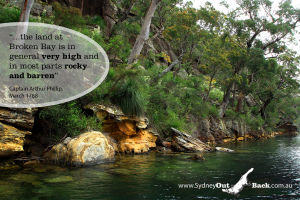

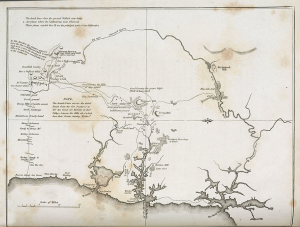

- Captain Arthur Phillip, Commander of the First Fleet and NSW’s first Governor (pictured), first explored Broken Bay within months, as a priority, of founding the colony of 1373 people in Port Jackson on 26 January 1788! (At this time, there was an estimated 2000 – 3000 Aboriginal people living on the coast between today’s Sydney Airport and Broken Bay, so the region’s total population multiplied exponentially in one day!) While searching for farming land and fresh water, Captain Phillip’s initial impression was that “the land at Broken Bay [was] in general very high and in most parts rocky and barren”* even though many waterways and coves were evaluated of good depth. Eventually, along the Hawkesbury River, they found the sought-after, fertile lowlands that were suitable for farming. By 1802, the region was mapped with remarkable accuracy as the heritage chart, below, shows.

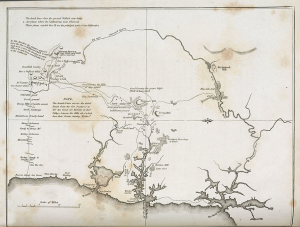

Chart of the three harbours of Botany Bay, Port Jackson, and Broken Bay, Neele sc. MAP RM 4079. http://nla.gov.au/nla.map-rm4079, from the National Library of Australia

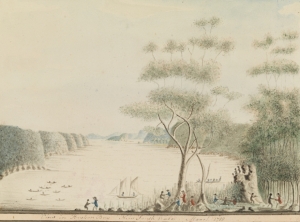

- Just over 238 years ago this month, on 5 March 1788 in rather gloomy wet weather, Captain Phillip and his crew landed HMS Resolute at an unnamed beach, later named Resolute Beach, in the shadow of West Head. His cordial interactions with a local indigenous elder on this first occasion include the elder’s compassionate supply of fire and repeated offers of shelter from the violent rain. One of the earliest illustrations of the March 1788 voyage shows festive interaction, possibly even dancing, between officers and Aboriginal men, with women safely observing from canoes off-shore.

“’View in Broken Bay New South Wales, March 1788” by William Bradley

- Captain Phillip did seek to treat Aboriginal people well; but fairly, in context with the wider colony, and he set injunctions that affected others to do likewise. He established humanitarian sanctions with punishments, including the colony’s most severe, for injury or murder of Aboriginal people under his Governorship. Captain Phillip was “leader” of the First, Second and Third Fleets (more than 4,000 arrivals in total by 1792) and had a missing front tooth which held symbolic value for the Aboriginal people. He truly believed through his power and influence, he could maintain harmony with the indigenous people while gradually impressing them with (and imposing on them) the superiority of British civilization

- By June 1789, inside two years of European arrival, smallpox was ravaging the local Aboriginal population and, during Captain Phillip’s third journey to Broken Bay, his second overland, he documented that innumerable indigenous people were suffering, dying or deceased from a disease that had barely touched the colonial immigrants. At the very least, 50% of the indigenous population (and possibly as many as 90% in the Sydney region) perished by 1830, while survivors fled inland tragically spreading the disease they sought to escape. By the end of 1792, due to his own deteriorating health, Captain Phillip resigned his commission and returned to London. With that ended the “honeymoon period”, and Aboriginal people realised with certainty that the colony of white trespassers were not following their “leader” “home” and were here to stay.

- The smallpox crisis devastated local indigenous clans – with many adults succumbing to the disease – so, severely weakened their resistance to the colonial occupation and cultivation of traditional lands. While Broken Bay’s topography repelled farmers and loggers, its untamed wilderness and secretive waterways easily clouded lawlessness and misdemeanor. It was ideal for camouflaging escaped convicts, rum smugglers (and any prohibited/restricted goods) and piracy of desperate outlaws. Legitimate traders, typically sloops carrying precious supplies of timber and food between the Hawkesbury and Pittwater (en route to Sydney Cove), travelled by necessity in small, armed convoys. Any remnant of Aboriginal clans indigenous to the region were most likely (as any reasonable person would become) angry, distrustful, fearful and defensive toward anyone unfamiliar, Aboriginal or not, they encountered.

- This indigenous remnant now also found themselves at a new frontier of conflict. In 1794, 22 farmers were settled on the lowlands to farm along the Hawkesbury and, with no road access for another 50 years. The waterways were now a colonial highway for transporting people and goods. The Aboriginal people now found themselves cut off from the river and waterways which had been their source of sustenance, food supply and travel for generations – and their bush trails were overtaken by armed military detachments sent to defend the farms from theft and attack by colonial escapees or exasperated Aboriginal people who found themselves continually driven from the few places left along the river where they could procure bush tucker, tools and bush medicine. By 1799, the homicide of Aboriginal people from this conflict resulted in a murder trial of five men, who were all later acquitted. In the minds of many Australians today, the Aboriginal people neither had a chance for peace nor a treaty that afforded them rights and dignity under the imposed colonial system… By 1830, records and historical journals concur that as few as 50 – 100 Aboriginal people had survived and remained in the region. And it was about to get worse: between 1788and 1850, 806 ships arrived carrying more than 162,000 convicts (with additional free settlers) from England.

Sydney OutBack traces its ancestry to the First Fleet. We acknowledge the many failings of colonial immigrants during the critical first years, with sadness. The colonial history we share seeks to be balanced, giving weight to the bad and not-so-bad interactions between the land’s traditional custodians, the Guringai Aboriginal people, and the European arrivals. We hope, in doing so fairly, we can show our ongoing respect for the Aboriginal people – past and present – and their enduring culture, with dignity and admiration. To learn more about Sydney OutBack’s Wilderness and Aboriginal Explorer Tour and Cruise, just click here.

Sydney OutBack traces its ancestry to the First Fleet. We acknowledge the many failings of colonial immigrants during the critical first years, with sadness. The colonial history we share seeks to be balanced, giving weight to the bad and not-so-bad interactions between the land’s traditional custodians, the Guringai Aboriginal people, and the European arrivals. We hope, in doing so fairly, we can show our ongoing respect for the Aboriginal people – past and present – and their enduring culture, with dignity and admiration. To learn more about Sydney OutBack’s Wilderness and Aboriginal Explorer Tour and Cruise, just click here.

Our tours are also part of Tourism Australia’s Indigenous Tourism Champions Program (ITCP), recognizing that we offer a quality experience that that meets the needs and expectations of international visitors.

To find out more about exploration of the Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park/the Hawkesbury region, more can be read online at *http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks/e00010.html (An Account of the English Colony of NSW Vol 1, By David Collins), and http://www.pittwateronlinenews.com/governor-phillip-camps-on-resolute-beach.php. To learn more about the First Fleet, visit http://www.fellowshipfirstfleeters.org.au/

0 Flares

0

Facebook

0

Google+

0

LinkedIn

0

0 Flares

×

Within 10 years of the First Fleet’s arrival in Australia on 26 January 1788, rapid exploration and settlement radiated out from Sydney Cove. In that decade, relations between colonial immigrants and the Indigenous population took several turns for the worse. Broken Bay and the region we now call Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park was one frontier where cordial first impressions gradually deteriorated, with devastating end-effect on the local Guringai people.

Within 10 years of the First Fleet’s arrival in Australia on 26 January 1788, rapid exploration and settlement radiated out from Sydney Cove. In that decade, relations between colonial immigrants and the Indigenous population took several turns for the worse. Broken Bay and the region we now call Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park was one frontier where cordial first impressions gradually deteriorated, with devastating end-effect on the local Guringai people.

Sydney OutBack traces its ancestry to the First Fleet. We acknowledge the many failings of colonial immigrants during the critical first years, with sadness. The colonial history we share seeks to be balanced, giving weight to the bad and not-so-bad interactions between the land’s traditional custodians, the Guringai Aboriginal people, and the European arrivals. We hope, in doing so fairly, we can show our ongoing respect for the Aboriginal people – past and present – and their enduring culture, with dignity and admiration. To learn more about Sydney OutBack’s Wilderness and Aboriginal Explorer Tour and Cruise, just click here.

Sydney OutBack traces its ancestry to the First Fleet. We acknowledge the many failings of colonial immigrants during the critical first years, with sadness. The colonial history we share seeks to be balanced, giving weight to the bad and not-so-bad interactions between the land’s traditional custodians, the Guringai Aboriginal people, and the European arrivals. We hope, in doing so fairly, we can show our ongoing respect for the Aboriginal people – past and present – and their enduring culture, with dignity and admiration. To learn more about Sydney OutBack’s Wilderness and Aboriginal Explorer Tour and Cruise, just click here.